School of Education

Radical Teaching in Turbulent Times

UD professor evaluates an alternate model for teaching from the 1960s

The college classroom has transformed over the last two years, affected by the transition to virtual teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic, today’s political climate and the Black Lives Matter movement and other protests. Some may regard today’s climate as similar to that of the 1960s, another turbulent time in American history that transformed the college experience.

As noted by Robert Hampel, professor in the University of Delaware’s School of Education, “Urgent issues of the 1960s continue to resurface today — racial equity above all, but also sexism, poverty, environmental deterioration and involvement in distant wars.” The soul-searching of the 1960s included reappraisals of what should happen in classrooms. “In both eras, we see heightened attention to the emotional and psychological health of college students. We also see soul-searching about the relevance of both old and new courses,” said Hampel.

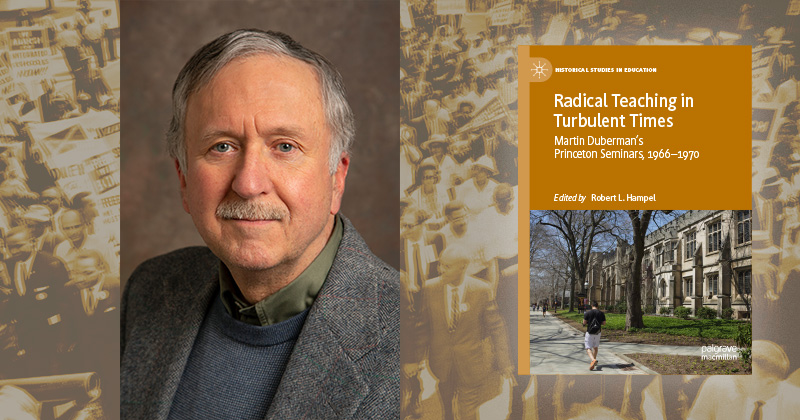

In his new book, entitled Radical Teaching in Turbulent Times: Martin Duberman’s Princeton Seminars, 1966–1970, Hampel traces the successes and challenges of Martin Duberman, a pioneering historian, who created an unstructured, experimental seminar on American radicalism at Princeton University. Through this study, Hampel evaluates an alternate model for teaching, inspiring educators to rethink the ways that they teach subjects in the humanities and social sciences.

Radical seminars

What made Martin Duberman’s history seminars so distinctive?

“In contrast to traditional models of teaching, Duberman dropped papers, tests, grades and mandatory attendance. Readings were optional and students chose the topics to discuss,” said Hampel, who is a member of the faculty in the College of Education and Human Development. “They spoke with Marty, not Professor Duberman, who thought traditional college classrooms encouraged bad habits: excessive deference, grade-grubbing and what he called the ‘spectator syndrome’—watching rather than participating. An advocate of group therapy, Duberman also encouraged the class to share their feelings and reflect on the interpersonal dynamics in the room.”

Though some educators may balk at a classroom without tests or grades, Hampel emphasizes that Duberman enacted many of the tenets that today’s professors continue to value. For example, many professors encourage active participation from their students so that their classrooms are defined by conversation rather than a one-way lecture.

“We know that students should not just sit and listen. The one-way transmission of information often turns students into spectators who quickly forget the material after the last exam. So, we encourage participation, offer choices, connect the curriculum with their lives, and try to spark initiative, curiosity and the intrinsic joy of learning,” said Hampel. “The passivity that Duberman deplored is less common today thanks to small group work, end-of-class writing, virtual office hours, interactive technology and other ways to engage students beyond taking notes.”

The relevance for today’s classrooms

As Hampel details in his book, Duberman’s experimental seminars were far from perfect. Some of Duberman’s students struggled with the unstructured nature of his classroom and resisted his model of education as self-discovery and personal fulfillment. Many students disengaged, cut class and stopped reading for Duberman’s seminar in order to focus on their other graded courses.

Despite these challenges, Hampel encourages educators to turn to Duberman as they ponder their classrooms. Duberman modeled perseverance and illustrated the reflective teaching that current teacher preparation programs emphasize: Duberman revised his seminar over time and reflected on his teaching by publishing articles on the seminar, writing long diary entries and discussing his work with a Princeton senior who wrote his thesis on the class.

“Few of us go as far as Duberman. No grades? No assigned readings? Surely chaos would ensue, with most of us driven by the fear that classes will fall apart unless we are in charge,” said Hampel. “For readers at odds with Duberman, this book might prompt them to take stock of why they avoid his preferences. For readers in accord with Duberman, the details of his experience will help them fine-tune their pedagogy. They should be reassured and inspired by the message that far-reaching pedagogical change is usually driven by deeply felt convictions and values, not a checklist or script.”

Radical Teaching in Turbulent Times: Martin Duberman’s Princeton Seminars, 1966–1970 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021) is available in hardback, paperback, and electronic formats from a range of retailers.

| Photo illustration by Jeffrey C. Chase

Read the full article in UDaily