School of Education

Leading the Way with Bookworms

Literacy curriculum developed by UD professor helps to eliminate the achievement gap in a Delaware school district

Imagine walking into an elementary school classroom where the students don’t want to put down their books. With enthusiasm, excitement and sometimes even frustration, these young readers — “bookworms” in the making — plead with their teachers for permission to read one more chapter.

In Delaware’s Seaford School District, this experience is a common one for elementary school teachers and principals. Six years ago, the district adopted the aptly titled Bookworms curriculum, an open access literacy program for kindergarten through fifth grade (K-5) teachers developed by University of Delaware professor Sharon Walpole and published online by Open Up Resources. Students’ love of reading and their literacy achievement exploded.

In 2015, Seaford ranked last among 19 school districts in Delaware with less than 32% of students achieving proficient scores on the state’s Smarter Balanced Assessment. Yet, in 2019, the percentage jumped to 53%, and during the challenging 2020-21 academic year, proficiency remained high at 41% — on par with the overall state average. Today, the school district remains one of the highest performing in the area of English Language Arts (ELA) in all of Delaware.

While many factors contribute to changes in student assessment scores, Seaford’s improvements in elementary ELA proficiency coincided with the implementation of Bookworms. Originally conceived by Walpole, professor in the School of Education, and her late colleague, Michael McKenna of the University of Virginia, Bookworms has become a national example for innovative, equitable and outcomes-driven ELA curriculum.

“The work with Dr. Walpole and the UD team represented a wonderful opportunity to engage in understanding the science behind how kids learn to read,” said Becky Neubert, principal of Seaford Central Elementary School. “We experienced putting that into practice and watching kids explode with their reading growth.”

What makes Bookworms unique?

In contrast to most ELA curricula, Bookworms uses full-length fiction and nonfiction children’s books rather than excerpts. The design recognizes that many children could be motivated to read, but the assignments they complete in school just aren’t engaging or challenging enough to hold their attention.

Bookworms also recognizes that engaged reading builds knowledge, and the amount of reading matters: a child will become a stronger reader with every book he or she reads. For this reason, Bookworms incorporates 265 whole books and emphasizes daily reading. Education journalists Natalie Wexler and Karin Chenoweth have counted Bookworms among the short list of knowledge-building curricula.

Bookworms is also unique in its instructional routines. All students — including those who have struggled with reading — read books selected for their grade level. In contrast to other curricula, these students do not receive simpler books. Instead, Bookworms supports these students using teaching routines based on research in literacy instruction.

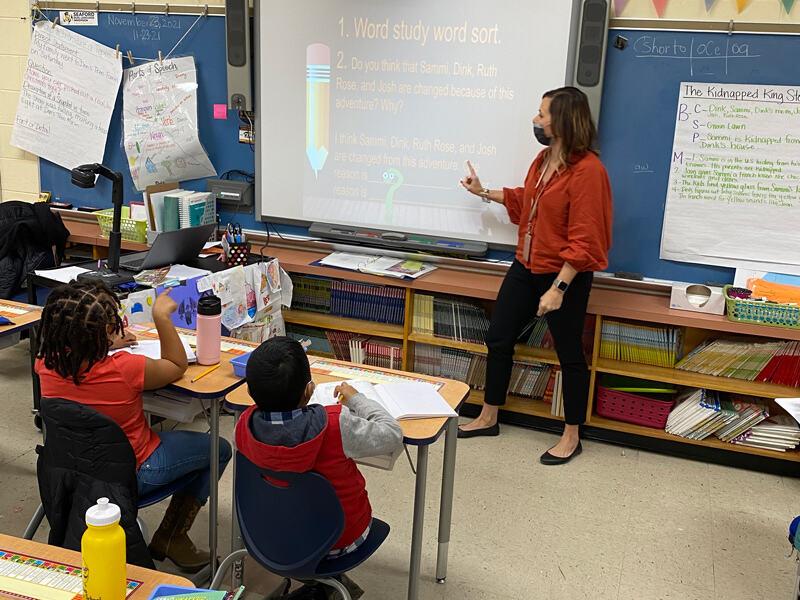

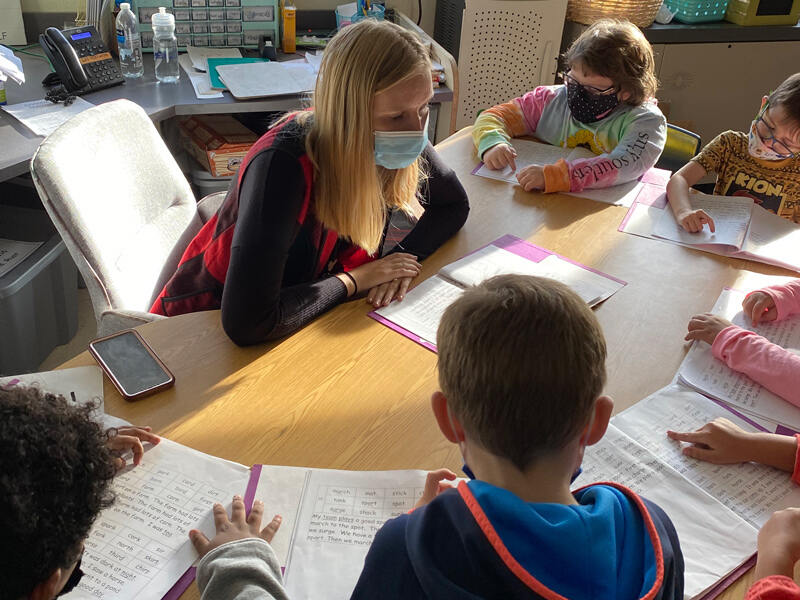

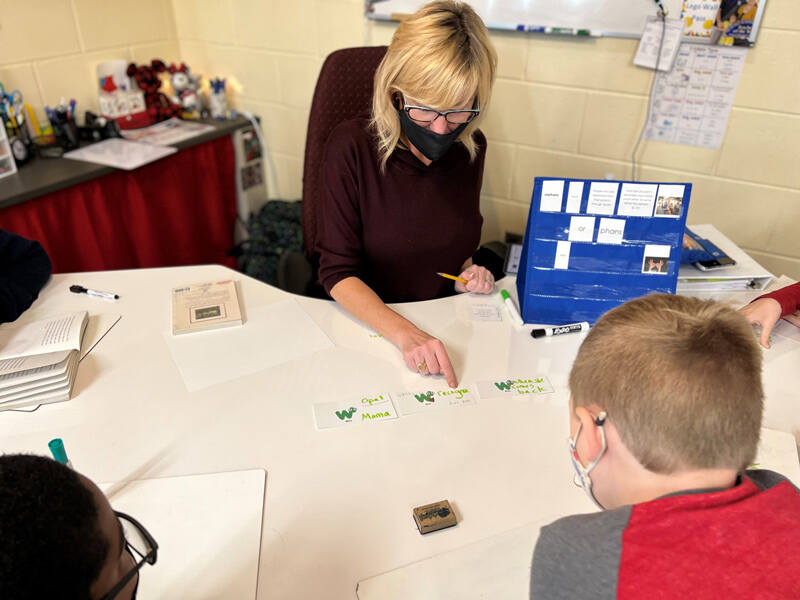

Bookworms teachers also provide specific attention to skills development. For example, simple assessments help teachers identify students’ word reading skills and short-term intervention help teachers address them. Bookworms operates with three 45-minute blocks: shared reading of those challenging books, English language arts to build grammar and writing competence and small-group, differentiated skills instruction. During differentiation, students may practice phonemic awareness and word recognition, complete fluency work or participate in even more engaged reading depending on their needs.

“I’ve never had such a comprehensive reading program that focused on both the early phonic skills as well as comprehension. In the past, it had always been one or the other,” said Krissy Jennette, principal of Blades Elementary School. “I think the combination of those two and the differentiated instruction time, which focuses on the specific skills of a particular student and what he or she needs at their level, is the beauty of it.”

Walpole also directs UD’s Professional Development Center for Educators and supports districts as they implement this curriculum.

“Typically, teachers are afraid that Bookworms is too hard, and they want their students to be successful. Bookworms is about students being successful with challenging tasks. It is very, very different from typical practice,” Walpole said. “Adopting Bookworms is a process. It means teachers have to let go of simple texts, and they have to let go of tasks and extensions that don’t point directly to increased achievement. Bookworms succeeds when teachers take the risk to do something really different and let children show them that they can do it.”

Success in Seaford

Data from Seaford School District provides one of the richest case studies of achievement increases on state tests when districts adopt Bookworms. In 2019, UD’s Center for Research in Education and Social Policy (CRESP) conducted a study of the implementation of Bookworms in the district and used statewide assessment data to track growth.

According to the report, literacy achievement for Seaford’s third graders was about 37 points lower than the state average in 2015. But, with the implementation of Bookworms, this cohort’s ELA scores grew at a rate of 18.9 points faster each year than other third graders in the state of Delaware.

By the time the Seaford cohort reached fifth grade in 2017, they had eliminated the achievement gap. Seaford’s students narrowly outperformed the state average: 61% of this cohort received proficient scores on the ELA Smarter Balanced Assessment, surpassing Delaware’s fifth-grade average of 60%.

“The really positive gains I observe in everyday instruction is what makes me most proud, and that’s evidenced in the critical thinking that’s taking place. The level of critical thinking that we see the students engaging in on a daily basis has really multiplied exponentially through the Bookworms curriculum,” said Kelly Carvajal Hageman, director of instruction in Seaford School District. “I truly believe that the Bookworms curriculum is not just a literacy curriculum, but a knowledge-building curriculum because it’s providing such a wealth of background knowledge for our students.”

Significantly, CRESP’s report also highlights how the curriculum contributes to equity in education, one of Walpole’s overarching goals. Seaford schools serve a population that is about 35% Black and about 26% Latino with about 17% qualifying for special education support. The data from CRESP’s report indicates greater ELA growth and greater overall achievement for students identifying as Hispanic, as African American and for students with disabilities in the Seaford District.

All student groups experienced growth with Bookworms. For example, in 2015, third grade ELA achievement for Hispanic students was, on average, 19.78 points lower for Seaford School District than for Hispanic third graders in the state. Between third and fifth grade, Seaford’s scores for this cohort grew at a rate of 26.74 points faster on average each year than the rate across the state.

In 2015, once this cohort reached the fifth grade, it surpassed the state’s average scores by 22 percentage points: 69% of this cohort’s students received proficient scores on the ELA Smarter Balanced Assessment compared to the Delaware average of 47%.

“We’ve steadily climbed since 2015, going from one of the worst-performing districts to being recognized by the federal government because our schools have had exceptional results,” said Corey Miklus, superintendent of the Seaford School District.

“The Bookworms story actually provides evidence that literacy research matters, and that strong pedagogy helps all children succeed — including those that we have often left behind,” said Walpole. “You can have curricula that address standards, but if they are not consistent with what we know about children’s literacy development and the specific instruction and practice experiences that accelerate it, it is unlikely to provide all children the chance to achieve rigorous standards. Leaders and teachers in Seaford decided that all children matter.”

What’s next for Bookworms?

Walpole is continually looking for ways to increase representation and has revised the curriculum twice since McKenna’s passing. In order for children to remain engaged, these young readers must see themselves in their books.

For example, the revised first-grade curriculum now includes the following culturally sensitive books about America’s past: Gerald McDermott’s Raven: A Trickster Tale from the Pacific Northwest, which builds knowledge of Native American culture; Verna Aardema’s Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears, which shares a pourquoi tale from West Africa; and Andrea Davis Pinkney’s Duke Ellington: The Piano Prince and His Orchestra, a biography of the famous jazz musician.

For the 2022-23 school year, Open Up Resources will release a new version of Bookworms with these and other changes. The new version will also include extensive support for teachers to discuss the complex issues inherent in many of the books.

For more information about Bookworms and implementation in your classroom, school or school district, visit the website for UD’s Professional Development Center for Educators.

Article by Jessica Henderson.

Photos courtesy of Seaford School District.

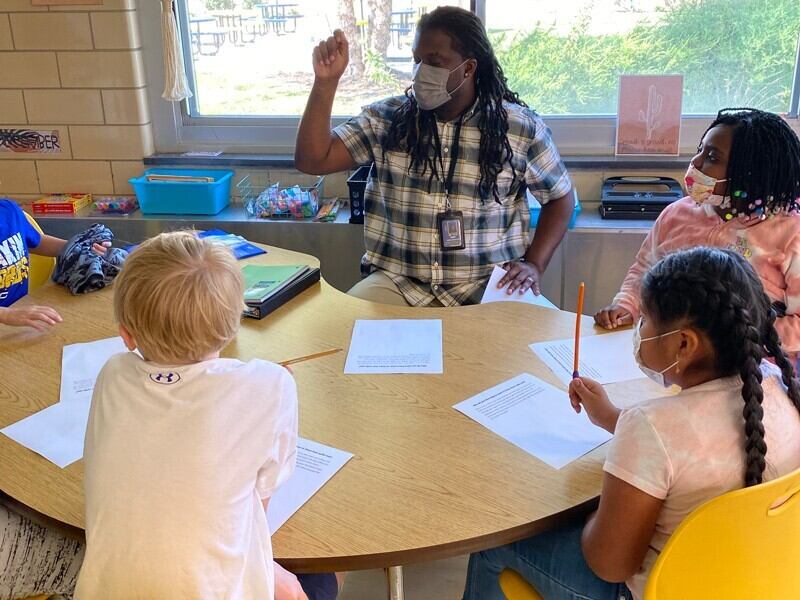

Feature image caption: Titus Mims, a reading paraprofessional at Central Elementary School, works with students during a Bookworms lesson.