School of Education

Brave Community

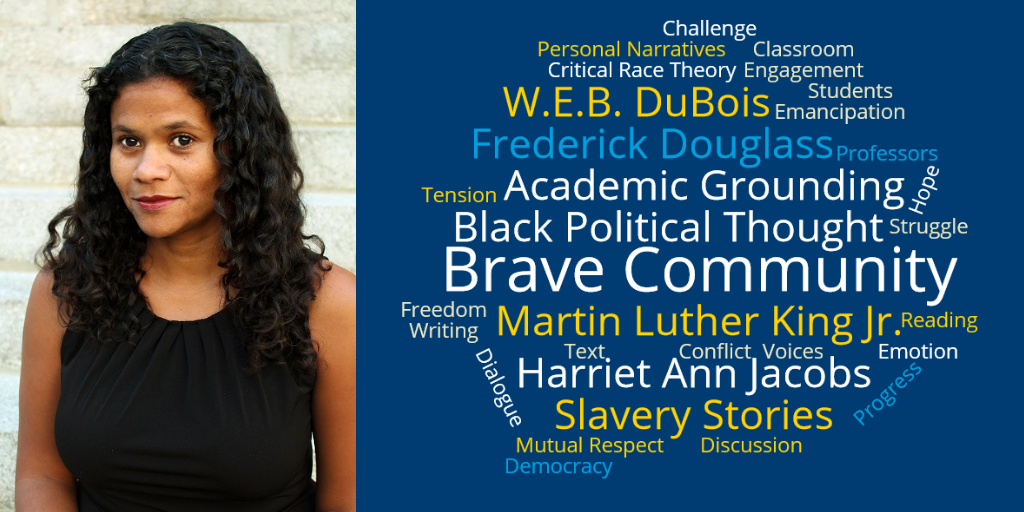

de Novais develops pedagogical approach for learning about race issues

In today’s political climate, marked by the Black Lives movement and other protests, conversations about race are difficult to have, especially as social media often fuels racial tensions rather than fostering productive dialogue.

“In lives dominated by the isolation and polarization of social media, college classrooms are fast becoming rare spaces where people can still engage with the complexities of a multicultural, unequal democracy face-to-face,” said Janine de Novais, assistant professor in the School of Education at the University of Delaware. “On the one hand, research has shown that college is indeed an optimal time to direct American undergraduates to confront the challenges, as well as the possibilities, of the country’s racial diversity. On the other hand, research evidences that learning about race in college, both in and outside of classrooms, can be fraught.”

Through her research, de Novais has developed a new theory of “brave community,” which describes the emergence of a classroom community that allows students to interact productively with one another as they engage with difficult content.

Developing a Brave Community

Through an ethnographic study, de Novais observed two courses, titled “Slavery Stories” and “Black Political Thought,” in an elite liberal college with curriculum centered on texts written by or about Black people. She interviewed students about their experiences engaging race in educational and non-educational contexts, their experiences in these courses, and whether issues or ideas from the courses emerged in their lives outside of the classroom.

Results from the study pointed de Novais to the central importance of academic grounding, or the integration of academic culture and expectations with academic content.

For example, one of de Novais’s participating professors opened the course with a frank acknowledgement that the course material would be intellectually and emotionally challenging. Yet, he expected the students to treat each other with respect, assume good intentions, remain fully engaged, and teach each other through lively dialogue.

“Both professors in this study employed explicit or implicit ways to signal to students that the classroom is a distinctive place, one requiring them to act in distinct, ‘academic ways’ to support the learning goals,” said de Novais. “One professor did this not only by stressing that mutual respect and engagement were necessary, but also by connecting their necessity to the challenging nature of the topic of slavery. He also invited students to take intellectual risks and hold the kind of discussion where such risks paid off.”

Such academic grounding allowed students to develop greater intellectual bravery and interpersonal empathy. It also helped students prioritize their academic learning as they worked to manage emotions and tensions during particularly challenging discussions.

De Novais has spoken about this research as an invited speaker at several universities and institutes, including Lesley University and the PZ Pittsburgh Institute for Teaching and Learning. She has also shared this work through the This Anthro Life podcast.

The study this article summaries is currently under review with an academic publisher.

Next steps at the University of Delaware

With a new grant proposal, de Novais hopes to introduce her University of Delaware colleagues to the “brave community” concept and classroom approach through a workshop for faculty.

In this proposed workshop, faculty participants will learn the brave community pedagogical approach, discuss a case study of racial tension in the classroom, and apply the approach to their own classroom contexts.

“I consider my research and practice to be part of a long line of work, rooted in a diasporic Black intellectual tradition, that pursues the end of racism as a core pedagogical aim and demonstrates a central aspect of why education is integral to democracy,” said de Novais. “I am passionate about researching good ways to translate those broad ideals into pedagogy and cultural practice. I think that all of the horrors of racism—which feel so overwhelming for us to tackle—actually occur at a very human scale, a daily scale, in relationships, in choices, in moments, and yes, in classrooms. I think we can do something, we can do better, and we just need to know how.”

Article by Jessica Henderson